patient resources

we understand the unmet needs of those living with ATTR

Transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) is a complex, rapidly progressive, and ultimately fatal condition that can affect many organs of the body, most notably the heart and nervous system. Non-specific symptoms and limited awareness often delay diagnosis of ATTR; on average, diagnosis occurs more than three years after initial symptom onset in elderly adults. This delay can have devastating consequences, and if left untreated life expectancy from diagnosis is approximately four years for ATTR patients with cardiac involvement.

Progression of ATTR often dramatically impacts the quality of life, functional independence, and life expectancy of patients, and creates a significant economic burden from the costs associated with progressively greater patient needs for supportive care.

our promise

We strive to establish and build enduring, supportive relationships with the ATTR community. We are committed to approaching these relationships with honesty, integrity, and transparency. We respect the independence of patient organizations and the unique perspective of every advocate, patient, and family member. We are working quickly to advance our drug development – knowing that every minute counts for patients and families affected by this devastating condition.

letters to community

At BridgeBio, we look to patients and advocacy groups to better understand the unique needs and experiences of individuals with genetic and rare diseases we hope to serve. We hope to give back to the community by providing updates on program milestones to increase awareness.

ATTRibute-CM Phase 3 Clinical Updates

In July 2023, BridgeBio announced that the ATTRibute-CM trial, a Phase 3 study for ATTR-CM, achieved its primary endpoint.

Learn morepatient resources

Every day, our work is inspired by patients and caregivers. Their partnership and collaboration are essential in understanding what’s meaningful and considering how BridgeBio can deliver medicines and services that fulfill the many unmet needs of patients. Learn more about our patient advocacy work by contacting [email protected].

Amyloidosis Alliance

Worldwide alliance of amyloidosis patient organizations and support groups looking to make contributions to the quality of care of amyloidosis patients.

Visit siteAmyloidosis Foundation

Patient advocacy organization committed to supporting patients and increasing awareness of all types of systemic amyloidosis.

Visit siteAmyloidosis Research Consortium

Global patient advocacy organization working to accelerate the development and access to new and innovative treatments for amyloidosis.

Visit siteAmyloidosis Support Groups

Patient advocacy organization dedicated to providing peer group support to patients, caregivers, families, and friends of those touched by amyloidosis.

Visit siteMackenzie’s Mission

Patient advocacy organization focused on raising disease awareness and supporting amyloidosis medical research.

Visit sitepatient stories

-

Phil's story

Prior to March of 2018, Phil rarely went to the doctor. In fact, he didn’t even have a primary care physician. At 71 years old, he biked 100 to 140 miles a week, swam, did triathlons, and ran marathons. Not only that, but his family had no history of disease—with some relatives who had lived into their hundreds.

But after developing sudden bladder pain and noticing blood in his urine, he made an appointment right away with a urologist. The good news: it probably wasn’t cancer. The bad news: he would need to see a cardiologist.

“I’ve got this bladder problem that’s keeping me up 14 to 18 times a night in excruciating pain. And they send me to a cardiologist?” Phil recalls thinking.

His heart tests revealed an unexpected diagnosis: transthyretin amyloidosis, or ATTR. The disease causes misfolded proteins to accumulate in organs, causing toxicity. While some forms of the disease are inherited, Phil’s was caused by age. This form of ATTR is known as wild-type TTR amyloidosis cardiomyopathy, or wtATTR-CM.

His heart tests revealed an unexpected diagnosis: transthyretin amyloidosis, or ATTR. The disease causes misfolded proteins to accumulate in organs, causing toxicity. While some forms of the disease are inherited, Phil’s was caused by age. This form of ATTR is known as wild-type TTR amyloidosis cardiomyopathy, or wtATTR-CM.“He’d be the last person that you would think would have cardiomyopathy,” says Phil’s partner Pam, who began accompanying Phil to his many doctor’s appointments.

At one appointment, Phil learned that his disease was causing irregular heartbeat—with periods of ventricular tachycardia, or an accelerated heart rate. To prevent any potentially fatal consequences, Phil’s medical team recommended a surgically implanted pacemaker. “Sick, old people have pacemakers, not someone like me who’s been active all my life,” says Phil, who conceded to his doctors’ advice.

While grappling with his new diagnosis and juggling hospital visits, Phil says he also struggled with uncertainty surrounding the progression of his ATTR: “how debilitating is it going to be for me? Is it going to impact my life so that I can’t do things I want to do?”

Yet, through this process, Phil has remained strong and positive—something he attributes to the support he receives from Pam and his ATTR support group. “I learned for the first time that when someone in a relationship gets a disease, you both have it,” he says. “I don’t know how I could have handled it if I was alone.”

Phil continues to be optimistic that a treatment will be available soon, hopefully in his lifetime, and stays abreast of the quickly-emerging medical knowledge about ATTR. “This is a good time to have the disease, if there ever was. And it’s only going to get better,” he says.

“Any disease can strike any one of us at any point, and you never know what’s going to happen,” Pam adds. “Phil’s got a really wonderful attitude about life and I think he’s a fighter. He believes in his body’s ability to heal. And I think those sorts of things, energetically, can really help.”

-

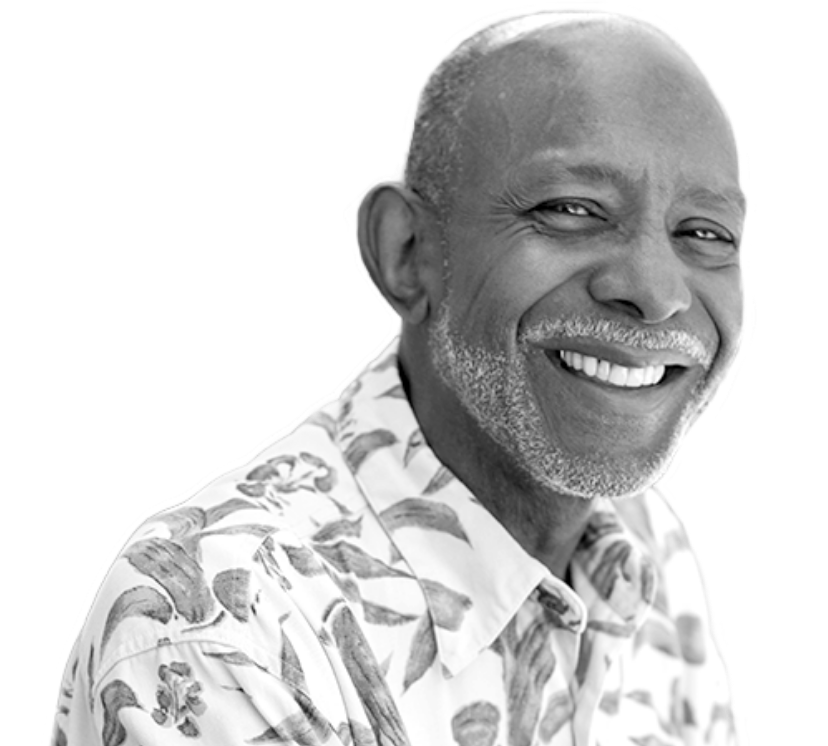

Art's story

Art, 75, recalls the many years he served on the local Police Department and coached high school football. Those were the years he would regularly hit the gym to lift weights or jump on his bike for a ride around town—before he ever knew about a devastating disease called transthyretin (TTR) amyloidosis (ATTR).

Today, Art’s life is very different. Not only does he know of ATTR, he lives with it. The disease means that Art becomes easily short of breath, even from a brief stroll or a walk up the stairs, and can’t participate in many family activities he once loved, such as camping.

“We used to have barbecues and invite friends over,” says the Northern California native. “It was an active life. And it just seems like boom, this happened so sudden. But I’m understanding now that it’s something that was building over the years.”

ATTR is a disease that occurs when a common protein found in the blood, TTR, becomes unstable and builds up in various organs. These buildups are toxic to healthy cells and can interfere with the normal function of the tissue.

He first suspected something was wrong in 2016 during a surprise anniversary party for him and his wife, Cheryl. He had recently gained 40 pounds, seemingly from fluid retention. Then, at the party, he had a hard time catching his breath. Visits to the cardiologist revealed atrial fibrillation, an irregular heartbeat that can be caused by ATTR. Doctors also drained excess fluid from his body, relieving uncomfortable pressure.

To identify the cause of Art’s condition, his doctors took tissue biopsies and identified TTR amyloid deposits. “The doctor told me I had amyloidosis,” he said. “I’d never heard of that before, and I wasn’t aware of a family history.”

While ATTR can be passed down in families, it can also occur in people who do not inherit a mutated gene. In these instances, the TTR protein is destabilized due to natural aging processes. This form of the disease is called “wild-type ATTR,” and it’s the type that Art has.

Doctors told him that the only true cure for the disease would be a double transplant: a heart and a kidney. He chose not to pursue that route, and instead chose to make the most of every day and find inspiration for the future. Art uses a scooter to get around, and continues to have fluid drained for comfort, as his kidneys aren’t doing their job effectively.

Doctors told him that the only true cure for the disease would be a double transplant: a heart and a kidney. He chose not to pursue that route, and instead chose to make the most of every day and find inspiration for the future. Art uses a scooter to get around, and continues to have fluid drained for comfort, as his kidneys aren’t doing their job effectively.Art says he has gained tremendous support from an amyloidosis patient group, where he’s met new friends and a new doctor who specializes in the condition.

“I’ll tell you, when I went to the first meeting, the biggest thing was just seeing others who have the same type of illness,” he said. “I wish that none of us were in a sickened state, but it was uplifting to know that I’m not alone.”

Today, Art is optimistic that a therapy for wild-type ATTR will reach patients within his lifetime.

“It’s been a journey down a very uncertain road,” he said. “I know there are others that are fighting [amyloidosis] and some who have already succumbed to it. It’s been an awakening for me to learn about it. And the more I learn about it and what is actually happening, I gain additional courage and strength to carry on.”

Art passed away from complications caused by ATTR in 2021.

-

Len's story

Len rarely passes up an opportunity for a new adventure. A world traveler with a passion for experiencing different cultures, he’s visited hundreds of countries and has dozens more on his list. But Len never expected the adventure he is on today — a journey that began in 2007, at the age of 64, with an unexpected diagnosis of a rare disease called transthyretin amyloidosis or ATTR.

“This is something you don’t sign up for, and it’s not easy” says Len. But despite the hardships, he has found a way to continue to live an active life and play an essential role in supporting other patients, putting his positivity to good use.

As Len remembers well, he was in the middle of a step aerobics class when he began experiencing the first signs of trouble: heart palpitations and dizziness. The symptoms were odd, as he and his wife Karen would exercise together four or five times per week and he never had any trouble keeping up with their vigorous routine.

As Len remembers well, he was in the middle of a step aerobics class when he began experiencing the first signs of trouble: heart palpitations and dizziness. The symptoms were odd, as he and his wife Karen would exercise together four or five times per week and he never had any trouble keeping up with their vigorous routine.He made an appointment with his family doctor, where an irregular heart beat prompted an urgent visit with a cardiologist. There, the evidence of ATTR became more apparent.

“I had an enlarged heart and thickened walls, so I was referred to a hematologist at Mayo Clinic,” Len says. “The first thing he asked me was: ‘is there any family history of amyloidosis?’”

The answer was yes. Len’s mother had both amyloidosis and Alzheimer’s. And while the latter seemed to garner more medical attention, Len slowly began to realize the former probably played the biggest role in her declining health before she passed away. Further tests confirmed that Len did indeed have hereditary amyloidosis, which was affecting his heart function. He learned he had the most common genetic variant of ATTR cardiomyopathy, Val122Ile or V122I. Approximately 4% of African Americans carry the V122I variant and Len was one of them.

Len’s form of the disease is often abbreviated as vATTR-CM, which usually manifests later in life. Over time, misfolded proteins accumulate in the heart, causing toxicity and life-threatening damage. When he was diagnosed, there was no FDA-approved treatment, which meant that Len would need a heart transplant to survive.

On March 8, 2008, Len’s name was added to the heart transplant list. And just about three months later, on June 10, his cardiologist called him with the good news: a healthy heart was waiting for him. Len headed straight to hospital. When he emerged from more than 11 hours of surgery, his new heart was beating so hard that it shook his hospital bed—even his wife could feel it. “What an experience,” he says.

On Christmas Eve of that year, almost exactly six months after the transplant, Len received a letter in the mail from the donor’s family. “The donor’s mother included pictures of her son and the rest of the family, along with the donor’s son, who was three-years-old at the time,” he says. “It was pretty dramatic.”

In the decade since his transplant, Len has made good use of his heart—living life to its fullest and giving back whenever he can. He and his wife have visited more than 71 countries and he has learned to handle the many strong emotions that come with having a disease without a cure. “The one thing my doctors have not told me is how long it would be before my new heart would be affected by the disease,” says Len, who continues to takes heart medicines to stay as healthy as possible. “They don’t have enough examples to be able to discern that.”

Len also connected with a college friend who coincidentally has the same form of the disease, and he is closely involved in a support group of amyloidosis patients, where he realizes how fortunate he was to have doctors who helped him find a diagnosis so quickly.

“New patients show up to the support group and are just devastated because they don’t know what to do or expect,” Len says. “Some of these folks are going to multiple doctors to get a diagnosis and are really afraid of this disease and what the future holds. It’s encouraging to know that companies are working to create a medication that might help prevent or slow down the disease.”

Len passed away from complications caused by ATTR in 2023.

-

Ivan's story

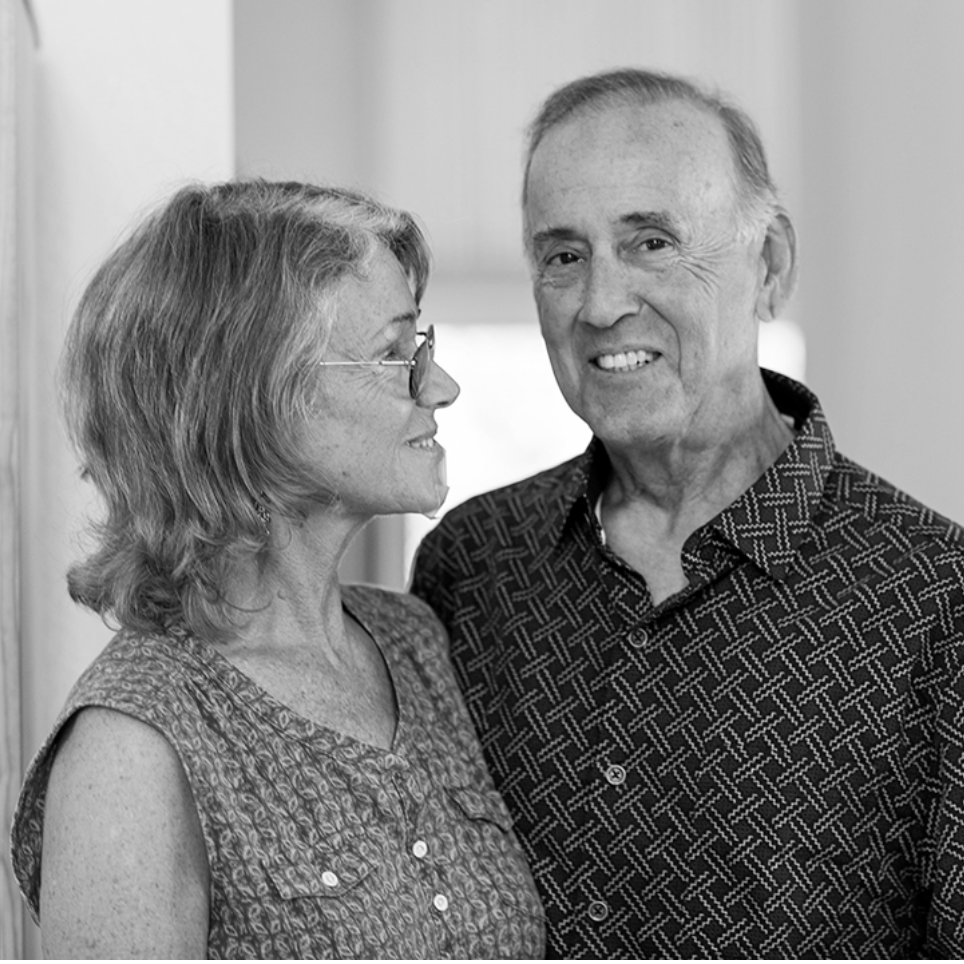

Even though they both worked in the medical field, Ivan and his wife Nora knew very little about a disease called transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) until Ivan was diagnosed with it. As with other rare diseases, finding answers about ATTR can be challenging for patients, not only because disease awareness is lacking, but because symptoms often appear over time and can easily be attributed to other conditions.

Ivan, a longtime physician, mistook the initial signs of ATTR for benign effects of aging. But after feeling out of breath from routine activities such as climbing stairs, Ivan suspected something more serious was going on. Up until then, he never had any trouble leading an active lifestyle—he and Nora enjoyed hiking, traveling, cycling, and cross-country skiing.

As his energy levels declined, and then after experiencing heart palpitations, he visited his doctor. A cardiogram test revealed a form of heart arrhythmia known as apical premature contractions, which is common in older patients: “it means you get an extra beat now and then,” Ivan says. He didn’t think much of it. However, over time, his arrhythmia became more frequent and his blood pressure gradually increased.

Five years after the initial presentation of his symptoms, Ivan’s cardiologist diagnosed him with a more serious heart condition, atrial fibrillation, which can lead to increased risk of stroke, heart failure, and other complications. The possibility of having ATTR still wasn’t on Ivan’s radar, though he soon learned that atrial fibrillation is common among patients with the disease.

Looking for answers, Ivan’s cardiologist ordered more tests: an angiogram and a cardiac biopsy. The results finally revealed the source of Ivan’s health problems. At 65 years old, he was diagnosed with the non-hereditary form of ATTR, called wild-type ATTR cardiomyopathy or wtATTR-CM. The disease affects roughly 300,000 people in the U.S.—although it is likely significantly underdiagnosed due to its nonspecific symptoms and a historical reliance on biopsy testing.

Ivan’s background in medicine has given him an edge in understanding the latest scientific literature about ATTR, including new therapeutic approaches that may one day treat the disease. For now, there is no way to slow disease progression. “The disease is inexorable,” he says. “It will continue to march on, no matter what you do.”

Ivan’s background in medicine has given him an edge in understanding the latest scientific literature about ATTR, including new therapeutic approaches that may one day treat the disease. For now, there is no way to slow disease progression. “The disease is inexorable,” he says. “It will continue to march on, no matter what you do.”Although he is no longer able to scuba dive or walk miles while traveling with his wife, Ivan says he still finds intrigue and adventure in different, more accessible ways. Together, he and Nora enjoy reading, spending time outside in their backyard, and keeping up with their two-year old granddaughter. “If anything, the disease has brought us closer,” says Ivan. The couple recently celebrated their 41st wedding anniversary.

“It’s disappointing that we can’t do some of the things we used to do,” he says. “But we still do interesting things together. We’re both still interested in biology—we can come out in the yard and find a jumping spider that’ll interest us both, and that means a lot to me. If you can take small things and enjoy them, you don’t have to hike the Appalachian Trail.”

Ivan has learned to embrace a slower pace of life, but says he has no plan of giving in to the disease.

“You do what you can to fight it, and hope that along the way you’re going to get some help,” he says. “So far, I’ve had help from my wife, my cardiologist and my internist. And, from what I’m reading, I think the pharmaceutical world is going to come up with some new medications that may help me even further.”